The Spanish transition represented a very important sea-change for the state’s political and social structure. Among other transformations, a new democratic system was established, which brought with it an unashamed opening-up towards a new way of understanding and making culture. A new generation of young artists faced a challenge previously impossible to imagine: breaking away from the old “clichés”, dismantling the old traditions associated with an oppressive regime and discovering the infinite possibilities that this new social context could offer them.

In parallel, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the most “underground” spheres of the music world, an explosion of creativity took place that in retrospect seems evident to me. One of the determining factors was, most probably, the introduction of the synthesiser into the “global” market: a new generation of electronic instruments were sold in specialist shops, and at prices now affordable for the general public. This meant, among many other things, that it was no longer necessary to join up with other musicians to form a band, or go to a recording studio to record a demo, or know how to play guitar to produce a song, or depend exclusively on a record label to release a record. Electronics were within everyone’s reach, punk was almost exhausted and something similar to a “new music” appeared from nowhere, or so it seemed.

New artists, new sounds… although they reached Barcelona in dribs and drabs, they showed a new way of making, understanding and above all listening to music that was total innovation; groups such as Ultravox, Joy Division, Kraftwerk, Tuxedomoon, Human League and so many others, incorporated among their instruments devices such as synthesisers, rhythm boxes and other electronic contraptions with a futuristic aesthetic that captivated many young people who were disenchanted and bored of always listening to the same music… And their discourse, close to the punk movement though more introspective or intellectual, fitted in perfectly with the everyday reality of this generation. We find ourselves in the midst of the Cold War, and the promises of a better world were now being discovered as the fallacies of an industrial society in decline. However, disillusionment was a widely extended feeling, especially among the younger generations. In short, a window opened up with infinite possibilities: a host of different, strange, and unknown sounds were available to disaffected young people who wanted to make a break with the past. And they didn’t need to be good musicians, or have a recording studio, or lots of money or even a minimum of musical knowledge; now they could do it.

An BCNmp7 to discover the new wave and industrial scene in Barcelona

The aim of this session is to find out and understand a little better how the music scene in Barcelona assimilated this new paradigm: through three pioneering musicians from our city we want to find out what or who inspired them to break with “musical” conventions of the time and how they did it; their relationship and/or connection with other groups and record labels, how they organised their concerts, how they advertised their music, how the public reacted to this “new music”, their perception of the media and the general public towards these “new sounds”, what problems or difficulties they had to face to continue with their projects and, in short, how the introduction of these new electronic instruments led them to do something that, at that time, very few people were doing in Barcelona, and with the few people that were doing it often ignored.

These three artists will be:

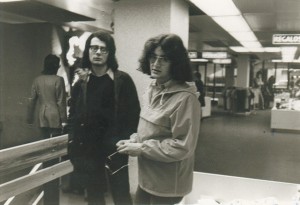

Víctor Nubla: one of the most important figures in experimental music in our country. A multidisciplinary artist with an inquiring mind, he is a musician, theorist, essayist, and experimentation activist. A writer, ideologist, programmer, publisher, cultural agitator and the creator, together with Jun Crek, of one of the leading industrial music groups: Macromassa. His career is a fundamental part of the avant-garde scene of Barcelona over the last thirty years.

Gat: musician and founder of leading and pioneering bands in Barcelona such as Ultratruita and later New Buildings, the latter more part of the New Wave movement. He was also founder of the G3G record label in the late 1980s; a project that initially emerged to cover the void existing in the artistic sphere. It was totally committed to the music scene, while far removed from the more commercial canons of the era. Pascal Comelade, Jakob Draminsky, Oriol Perucho, Macromassa, Raeo (Mark Cunningham), Pau Riba, Juan Crek… these are just some of the names that among many others are listed in its wide-ranging catalogue.

J.J. Ibañez: Founder of Badalona-based group Kremlyn in the early 1980s and also a very active artist on Barcelona’s electronic scene in the early 1990s. Kremlyn was a band that could be considered as Technopop which, although not managing to record any albums, was very active between 1982 and 1986. Nowadays we can consider Kremlyn as one of the few Catalan music bands categorised in the Technopop style, especially from Barcelona, with a very genuine and interesting sound. Last year Domestica Records released one of its first live concerts, with a very warm welcome among the younger audience, and an LP with studio songs is planned for next year.

Immediately following this we can enjoy, for the first time in Barcelona, performances by two representatives and heirs of this “new” scene:

Tvnnel: A low and deep voice, acidic and nostalgic lyrics diluted in the coolness of programmed sounds and rhythms. TVNNEL was born in 2013 as a solo project by artist Tono Inglés (Polígono Hindú Astral, Roman skirts). Three synthesisers and a hardware sequencer submerge us in an underground tunnel, where dance and melancholy converge. Trying to move away from “revival” proposals, TVNNEL seeks new paths between electro, synth pop and industrial music. Machine coolness and human warmth combined in an interesting and personal proposal, with a musical idea and a staging that clearly seeks reduction, minimalism, and self-production.

Phillipe Laurent (France): plastic artist, musician, and designer active since the early 1980s, he now has a very extensive discography and audiovisual production and is one of the most internationally renowned names on the Minimal-Synth scene. Whether working with graphic codes or digital codes, plastic arts or music, Laurent’s focus and objective is always investigation into people’s perception of signs and symbols. As a multimedia artist, Laurent has always been an innovator, incorporating new technologies to compose graphic and music works. In the 1990s, his work achieved maximum dissemination with a series of concerts in France and Germany through the design of complex pieces that mixed different advanced techniques. His paintings or the illusory effect of typographies on a monochrome background raise a question regarding the relationship between signs and meanings. Philippe Laurent develops abstract ideograms, with the aim of never repeating the same figure twice, in the same way that the writing of a lost continent or of an original language was a code that preceded all other languages and has now been lost. This play on ambiguity sparks a fundamental question on the ontological status of written language in our western societies. Philippe Laurent has developed a wide-ranging personal study of the forms of the first symbols and letters that lead to the “sublimity” of an esoteric alphabet.

More information on the Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/1376191062655896/?fref=ts