“1,000 m2 of Desire: Architecture and Sexuality” explores how architecture has defined our spaces for sex. With its backdrop of two revolutions, the French revolution of 1789 and that of May 1968, the exhibition traces a historical route through literature, art, architecture, design and mobile apps. In order to make sure that you don’t get lost among the 250 pieces in the 1,000 m2referred to in the title, we have made a selection of essential works which, in themselves, deserve to be seen for their historical importance, and because they are unique, curious or especially constructed for the exhibition. We offer an assortment of books, models, plans and drawings, engravings and reproductions of spaces in real scale so that you can immerse yourself in a different world and, at the same time, make a journey through time in the architecture of desire.

Playboy, a Magazine for Lovers of Architecture?

“The playboy and his magazine are all about architecture,” writes the architect Beatriz Colomina in a text of the exhibition catalogue. The fact is that, although this publication was (and still is) a reference of eroticism, one of the aims of its editor Hugh Hefner was that it should also be a reference of style, architecture and design. The Playboy man had to live in an apartment designed for seduction, in a loft without doors or rooms so as to keep the woman constantly on view. Accordingly, some of the best architects and designers of the day, from Charles Eames to Eero Saarinen, occupied page after page of the magazine, together with naked girls, articles by Truman Capote and interviews with Michael Caine. In #expodesig you will find a space devoted exclusively to Playboy magazine and curated by Beatriz Colomina and her team. Here you can explore models of the Playboy mansion and Hefner’s private plane, stretch out on his round bed, read articles on the architects in vogue, and look at plans of the most amazing houses of the day, some of which were used as film locations, as for example in the James Bond series.

Pornography According to Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne

Did you know that the word “pornography” made its first appearance in 1769? To be more specific, it made its debut in a treatise by Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne, a writer who, in his work Le Pornographe (a neologism he coined to designate someone who writes about prostitution), describes in lavish detail what an establishment devoted to prostitution should be like, or estimates the worth of each girl according to her age and beauty. For Restif de la Bretonne, pornography was an affair of state and his proposal was innovative and audacious when you consider that he was writing in pre-revolutionary France. These establishments, called Parthénions (houses for young virgins) had considerable influence in the theories of Charles Nicolas Ledoux, whose work is represented by numerous items in the exhibition, including the famous Oikema. The original of Le Pornographe is exhibited here.

The Polaroids of Carlo Mollino

Carlo Mollino was a prestigious Italian architect who was also active in other disciplines including literature, automobilism, aeronautics and furniture design. But, most of all, he was interested in photography. After his death in 1973, his heirs discovered a hitherto unknown collection of photographs: elegantly naked women in a collection of portraits Mollino had been working on throughout his life. The Polaroids were taken in his own apartment, where he had a set which he readied for each occasion. The women were chosen in the street or the brothels of Turin, the city where he lived. There is not a single repeated portrait and every staging is different in a total of more than 1,000 fetishist poses recorded in 8 x 10 cm. which you can discover in a semi-darkened chamber.

The Original Plans of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon

Universal suffrage, the separation of church and state, abolition of slavery, animal rights, sexual freedom, women’s lib, and decriminalisation of homosexuality: Jeremy Bentham was a trailblazer championing ideas which are nowadays on everyone’s lips. Among his great contributions is the idea of the Panopticon, the architectural figure of power in modern society, an “inspection house” applicable to any institution—for example, prisons, hospitals or schools—which enabled constant monitoring of inmates. The structure of the Model Prison in Barcelona is based on the Panopticon as defined by Bentham in 1791. However, Jeremy Bentham was not an architect but a philosopher, so the original plans of the Panopticon shown in the exhibition are by Willey Reveley. By the way, if you care to know what Bentham (literally) looked like, you can go and visit his fully-dressed mummified corpse at University College, London.

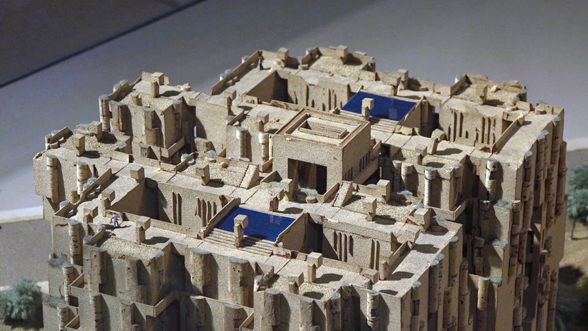

The Sketch of Charles Fourier’s Phalanstery

The utopian philosopher Charles Fourier was a contemporary of Jeremy Bentham’s and, like him, was a revolutionary, though he was also a utopian who believed in human goodness and that it was possible to create a sexual paradise in which every passion could be recognised and satisfied. This blissful place was called Harmony and the phalanstery was the setting for the gratification of all passions. Occupying five square kilometres of cultivable land near a forest and a big city, it was designed with three floors and three wings, each one for fulfilling sexual desires. The idea was adopted by hippy movements of the 1960s, but there are further examples in architecture such as the Walden 7 building by Ricardo Bofill (the form of which, by the way, is reminiscent of a vagina), geodesic domes (like the one at the creation centre of the theatre group Els Comediants in Canet de Mar), and also the utopian cities designed by the Archigram architectural group. In “1,000 m2 of Desire: Architecture and Sexuality” you will find the original drawings of the phalanstery and also the original model of Bofill’s building.

Engraving of the Sacrifice of an Ass in Honour of Priapus from The Dream of Poliphilus

This is every bibliophile’s dream. An enigmatic book, of uncertain authorship, bringing together all kinds of medieval knowledge from mythology to chess, astronomy, liturgy, epigraphy, archaeology and the art of pruning brambles, The Dream of Poliphilus (https Hypnerotomachia Poliphili), published in 1499, tells the story of Poliphilus, who dreams of recovering his beloved Polia as he crosses imaginary landscapes of fabulous architecture. This is one of the first examples of a work combining architecture with eroticism. It contains 171 of the author’s woodcuts, among them “Sacrifice of an Ass in Honour of Priapus”, which is shown in the exhibition. The book, dedicated to the Duke of Urbino, was financed by the aristocrat Leonardo Grassi, Apostolic Protonotary, an architecture enthusiast and the man responsible for the fortifications of Padua, and printed in Venice by Aldo Manuzio, one of the most renowned printers of the day. It is almost as if Planeta had published a book dedicated to Count of Godó and financed by the Güell family!

Nicolas Schöffer’s Centre for Sexual Leisure

Imagine a space devoted solely to pleasure, pampering all five senses. A space where light, smells, and colours are intended to stimulate your senses and prepare them for sexual intercourse. This is the Centre for Sexual Leisure which the plastic artist and sculptor Nicolas Schöffer designed for his cybernetic city (1955 – 1969), a utopian city project inspired by Fourier. Like other utopian ideas, it never materialised but in the exhibition you can see a real-scale reproduction of this space: a closed room in which light, textures, geometric metal sculptures and music appear as the lead players so that the visitor can experiment with all the senses. This is an experience which requires an open mind.

A Second (Virtual) Life

Imagine a space where you can live life as you wish. Where you can give free rein to all your most perverse desires. Where you can imagine your penis taking on impossible shapes, or that you yourself have an impossible form allowing enjoyment of unknown pleasures… Second Life started out as a virtual world in which, by means of an avatar, users can interact with other avatars and construct their own world but this has become a territory without norms and without taboos where users can organise sexual encounters in settings that reproduce the architecture of their sexual fantasies right down to the finest detail. Well, this all happens in a virtual space. In the exhibition you can see a video showing one of these digital spaces designed for sex.

Rem Koolhaas’s Baths

Centre of London. Spreading out from the wall that delimits it, a level space is divided into eleven zones, among them a ceremonial square, the Park of the Four Elements, with temples for sensuous experiences, the Square of the Muses (where only the British Museum survives), and the baths. Inspired by Ledoux’s Oikema, these baths have zones of observation, exhibition, seduction and meeting (the pools) as well as cells for consummation in which photograms from a pornographic film The White Slave are projected. This utopian dream of the architect Rem Koolhaas, Pritzker Prize winner and designer of the iconic China Central Television tower, dates back to the early period of radical architecture in the 1970s. The exhibition shows the original drawings and plans of Koolhaas’s idea.