Irene de Mendoza © CCCB, 2017. Elisenda Pallarés

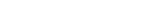

The best-known photobooks are those that we make ourselves with photos of our holidays and that we show to friends and family on our return. At the “Photobook Phenomenon” exhibition, the term “photobook” adopts another dimension and historical significance. The photobooks exhibited at the CCCB and at the Foto Colectania Foundation are creative projects, stories in images, graphic accounts of the visual culture of our times. They are artistic objects where the creativity and choral work of many professionals (designers, printers, illustrators, photographers, etc.) all come into play. Their themes are as varied as suicide and the story of Spain’s first serial killer. They can also have different formats: from a traditional book to a cigarette pack or a Chinese sewing box. However, not all these photobooks contain photographs taken by the author; some contain archive images, photographs purchased at flea markets, drawings, etc.

At the height of the digital era, more photobooks are being published than ever before, and increasing numbers of professional find in this formula a pathway for expressing themselves and telling stories. “The photobook has the capacity to change the lives of these people” affirmed collector Martin Parr at the exhibition’s opening event.

We talked about the diversity and richness of photobooks and the fundamental role they play in heightening visibility of the work of contemporary artists and photographers with Irene de Mendoza, artistic director of the Foto Colectania Foundation and one of the curators of the “Photobook Phenomenon” exhibition.

Elisenda Pallarés: These days we can talk about the appearance of the “photobook phenomenon”. Many circuits and festivals exist dedicated to this format where artists and collectors make themselves known. This is not the first exhibition on this subject, so what is different about “Photobook Phenomenon”?

Irene de Mendoza: The “Photobook Phenomenon” exhibition produced jointly by the CCCB and the Foto Colectania Foundation aims to move away from the classic exhibition of photobooks by a photography centre. Exhibitions have already been held internationally on this subject, but always from the viewpoint of the photography. This time we have ventured to talk about the photobook in more general terms, as the exponent of the visual culture of an era, following to a certain extent the example of the Tate Modern, which has just acquired Martin Parr’s collection. We should not understand the photobook as exclusively an art of photography; it is an art that embraces many more disciplines. A key feature of the exhibition has been having seven curators who have presented very different themes.

EP: There are many women authors in the contemporary photobooks section. However, the same does not occur with the other sections. Is the world of the photobook a world of male creators and collectors?

IM: It is true that proportionally we find more men, even though history is full of women photographers. This is also reflected in the art world and in curatorship. However, now we are experiencing a total change, above all in the area of creation, where very powerful female photographers are starting to make their names known. In Spain, there are more women than men enjoying international recognition, as is the case of Cristina de Middel whom Martin Parr always cites as a reference artist. She consolidated her career starting with the self-publishing of a book.

EP: Does the same happen with photojournalism? Right now the exhibition World Press Photo is being presented in Barcelona and every year we observe more male prize-winners than female ones.

IM: It has always been more difficult for women in every sphere. Joana Biarnés, considered the first Spanish female photojournalist, is a good example. The documentary Joana Biarnés, una entre todos explains the difficulties she had to overcome to become a photographer. Although proportionally there have always been more male photographers it is also true that it has been easier for them to make themselves known. We don’t know if, in the future, archives will be found of unknown women photographers, as in the case of Vivian Maier, who spent her whole life taking photographs but never disseminated them.

Irene de Mendoza © CCCB, 2017. Elisenda Pallarés

EP: The exhibition features photobooks in different formats, from the more traditional book to Xian, by Thomas Sauvin, in which each reader takes a different journey and, consequently, has a different reading. What differentiates photobooks?

IM: At the height of the digital era, photographers have found in the photobook the ideal medium for showing a project in a coherent way. On the Internet the tendency exists for photographs to be circulated and separated from their context. The photobook, however, is something physical that enables coherence to be given to a project and allows artists to experiment with the format, the paper, deciding on the cover, etc.

The dream of authors who create photography books is for people to consider them like a novel: with a cover, a title, an introduction, a core and a denouement. There are also authors who break with this line, but it should still be understood as a reading. Often we start leafing through a book of images from the end, but nobody starts reading a novel from the end.

EP: The creation of the photographic book is a collective endeavour.

IM: Yes, it is a choral work. Often we relate it with the world of cinema. In a film, the director obviously plays an important part but the film is the result of the work of an entire team. In the creation of a photobook, the designer or the editor, for example, also play an extremely important role. Moreover, younger people have received a better education, they travel, speak English and use social media networks and all this is reflected in their work.

EP: What prominent names do we find among this new generation of Spanish photographers?

IM: There are major authors such as Carlos Spottorno, Cristina de Middel, Ricardo Cases and Óscar Monzón, who won the Paris Photo with Karma. All of them are internationally recognised for their photobooks. And also Laia Abril and Julián Barón, whose most recent works we can find at the exhibition.

EP: How do they make their work known?

IM: Through the book. Twenty years ago they thought more about doing an exhibition and making a catalogue as a record of the exhibition. But an exhibition is more limited. Which is better: an exhibition in Berlin, for example, or publishing a book that will also be seen in the MoMA bookstore? These photographers aim to reach a lot of people and they focus on this. Also, today, all the photography fairs and festivals devote a significant section to the photobook.

EP: Are there talent-spotters in the world of the photobook?

IM: Yes, there are gurus or opinion leaders, such as Horacio Fernández, Gerry Badger and Martin Parr, and we have been lucky enough to see many of them at “Photobook Phenomenon”. But we must not forget the fundamental role played by the publishers. In this case, Editorial RM, with whom we have co-published the exhibition catalogue, are spokespersons and supporters of projects. They personally take the books that they publish to the major opinion leaders in the world of photography.

EP: Apart from the viewpoint of these opinion leaders, is there space for participation in the world of photobooks?

Yes. “Photobook Phenomenon” shows that the world of the photobook is not relegated exclusively to photography as a speciality. The photobook is not something exclusively for artists of photography, but the subjects dealt with can spark anyone’s interest. It is a vehicle that uses photographs, or images – because these days talking about photography means talking about images – to deal with very diverse issues. At the exhibition, many photobooks can be seen whose images were not made by the author, following the line of post-photography, so widely written about by Joan Fontcuberta. Photos from public or private archives are also published.

The idea is to narrate using images and this connects very well with the era in which we live. Between getting up and eating lunch we receive more visual impacts than a 14th century person received in their entire lifetime. There is a tsunami of images. I think that all those people who tell stories through images have a fundamental role to play. In the field of education there is still much to be done, because visual language is not being taught. However, many young people communicate with each other using this language: they no longer write about what they are doing, they send a photo. That is what is happening today, we communicate through images.

EP: In the section on contemporary practices you highlight the work of Laia Abril, Julián Barón, Alejandro Cartagena, Jana Romanova, Vivianne Sassen, Thomas Sauvin and Katja Stuke & Oliver Sieber. Why did you choose these authors?

IM: We have tried to select a series of authors who not only have created interesting photobooks, but for whom the photobook is almost their identity. As Moritz Neumüller says, they live for and with photobooks. They are artists who have found in this format the most coherent way of expressing themselves, and we have asked them to explain the book’s creation process.

EP: As a finishing touch to the exhibition, there is the Espai Beta with 150 photobooks published over the last two years. Can you tell us about some of them?

We were very sure that we wanted to create a reading space at the Espai Beta that would reflect the effervescence in contemporary photobook creation. You can find such marvels as Silent Histories by Kazuma Obara. The book explores the consequences of the Second World War in Japan, a subject that has received little coverage. It tells the story of a group of people through their own accounts, with archive images, current photographs and other elements such as a passport or the drawings of a lady who was only able to tell her story through them.