(Català) Tornar al món (o per una nova relació amb la naturalesa)

August 31st, 2016 Anna Punsoda No CommentsGandules Nights at the CCCB: Nights of Films and Sins

July 14th, 2016 Elisenda Pallares 1 CommentThis year’s cinema al fresco season is based on true confessions: I have sinned. Gandules’16 Gas Natural Fenosa is dedicated to the seven deadly sins: lust, sloth, gluttony, anger, envy, greed and pride; and two extra ones for free: sadness and extreme fantasy, courtesy of Desirée de Fez, the programmer of this edition.

“For Gandules’16 I have programmed nine films thinking about what I would like to see as a viewer at an al fresco film cycle accompanied by friends and in a relaxed atmosphere”, explains Desirée de Fez. The film critic has made a varied selection with titles such as Amenaza en la sombra by Nicolas Roeg (Don’t Look Now, 1973) and The Room (2003) by Tommy Wiseau, considered “one of the worst films in history” by many film critics.

The deadly sins are considered the origin of all the mistakes that humans may ever want to commit. According to Saint Thomas (II-II:153:4), “a capital vice is that which has an exceedingly desirable end, so that in his desire for it a man goes on to the commission of many sins all of which are said to originate in that vice as their chief source.” The list of capital sins that must be avoided according to Christian morals has varied over time. Originally there were eight, including sadness. It was in the 6th century that Pope Gregory the Great established the number of sins as seven, as he considered sadness as a form of sloth.

Nine sins, nine films

Desirée de Fez has aimed to claw back sadness and has also included extreme fantasy in the programme. “Nowadays we all sin. The seven sins that we have known all our lives are no longer sufficient,” she affirms. Gandules’16 offers the viewer nine films that are each connected with a sin, sometimes in a subtle way. And no, Seven (1995) is not to be found among the films chosen.

The season begins on 9 August with Laberinto de pasiones (1982), one of the first films by Pedro Almodóvar, an invitation to lust that, for de Fez, “sketches a part of the social history of the 1980s”. Sloth is represented by Movida del 76 (Dazed and Confused, 1993) by Richard Linklater, and gluttony by Joven y alocada (2012), by Chilean Marialy Rivas, a film that deals with sexual discovery. De Fez has chosen Babadook (2014), by Jennifer Kent, to represent anger and to give a second chance to this horror film which has not previously enjoyed “the repercussions that it deserves”.

We can enjoy less well-known productions such as El rapto de Bunny Lake (Bunny Lake Is Missing), by Otto Preminger, for the sin of envy; and El gran rugido (Roar, 1981), by Noel Marshall, for greed. “In this film, a young Melanie Griffith was attacked by a lion and had to undergo reconstructive surgery”, de Fez notes.

For its final week, Gandules proposes the inclement melodrama The Room (2003), by Tommy Wiseau, representing pride. Plus the subline Amenaza en la sombra (Don’t Look Now, 1973), by Nicolas Roeg, with an ode to sadness. And Valerie y su semana de las maravillas (Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, 1970), by Jaromil Jires, as the culminating film representing extreme fantasy.

Desirée de Fez is of the opinion that it is possible to commit sins in a gracious way and she invites us to discover these tales and their meanings, simply choosing a little escapism on these summer nights. Each screening will be preceded by a video where musicians such as Joe Crepúsculo, film critics such as Manu Yánez or director Juan Antonio Bayona confess to us those aspects of the film that have seduced them most.

From 9 to 25 August, every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, you are invited to cool off at 22.00 in the Pati de les Dones. Admission is free of charge and capacity is limited. Until Gandules’16 arrives, you can also succumb to desire with our list of sinful songs on Spotify, where you can add your own proposals. The songs proposed by you will be played as the soundtrack to the al fresco cinema sessions before each screening.

Llull the contemporary

June 30th, 2016 Eva Rexach No CommentsIf Ramon Llull were alive today he would be at the top of the best sellers’ list. He would be one of the stars at Barcelona’s Comic Fair where he would have been invited as a pioneer in the genre. He would be taking part in discussions about multiculturalism alongside Arabic and Jewish thinkers. He would be giving poetry readings and a travel agency would have been named after him. If Ramon Llull were still alive he would remark, with pride, that 700 years after his death, his work is not only valid but has taken on truly global proportions thanks precisely to the web, a technology he can be considered the forerunner of.

Breviculum’s animation, Ramon Llull life’s illustrated work. Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, Cod. St. Peter perg. 92

Ramon Llull is a fascinating character but he is still surrounded by an aura of incomprehensibility and unfathomability. We have a somewhat biased image of Llull, of a man trapped in the dark and terrible Middle Ages, when, in fact, the reality was quite different: Llull lived in an age that saw the building of the first cathedrals which sought out light and colour, and he travelled around some of the foremost cultural hubs in Europe and the Mediterranean.

One thing is true however: the fact that we are devoting an exhibition to Llull today, seven centuries after his death, at a centre for contemporary culture, is because his thinking remains relevant today. Because, beyond his obsession with God, what he endeavoured to explain throughout his life (a new way of thinking) is still valid across many disciplines. That’s why, in order to gain a greater insight into Ramon Llull and his thinking, we have chosen a number of ideas to undo this image.

Ramon Llull lived a courtly and elitist life until the age of 30

Ramon Llull was from a well-to-do family and, as such, he lived a comfortable life and had connections with the court of King Jaume II of Mallorca. He married Blanca Picany when he was about 25 and they had two children, Domènec and Magdalena. It would appear that Blanca wasn´t the only woman in his life as, at the time, Ramon Llull was writing troubadour poetry and some people say that he lived quite a rakish life. All this changed when Ramon was 30 years old and, while he was writing one of these poems, Christ appeared to him on the cross. The vision, which reoccurred up to four times, changed his life.

Ramon Llull wrote the same book throughout his life

From this moment on, Ramon Llull lived the life of an enlightened person. He left his wife and children and withdrew to live as a hermit for four months at Puig de Randa (Mallorca), where he received the divine appointment to write “the most beautiful book in the world”. And he devoted himself to this task for the rest of his life. In fact he wrote more than 250 books that are just variations on the same book. The word of God is the book.

Ramon Llull wrote true bestsellers

The Book of Contemplation is a thousand words long and four times longer than Tirant lo Blanc. Llull is the medieval author of the largest surviving number of medieval manuscripts, many of them written during his lifetime; there are more copies of his works than by Thomas Aquinas, and Giordano Bruno wrote up to six treatises inspired by Lullian thought. The Ars Brevis, a summary of his philosophy, was copied more times than Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Ramon Llull is the main character in the first comic of all time

The Breviculum is an extraordinary work: a true medieval comic that tells the story of Ramon Llull’s life in 12 miniatures. It was made around 1321 by Tomàs Le Myésier, a follower of Llull’s who was associated with the French court, and includes the characteristic balloons with the words of the people depicted inside. It is kept at the Badische Landesbibliothek in Karlsruhe, and you can see an animated version at the exhibition.

Ramon Llull was a tireless traveller

Our central figure was also a travel pioneer and undertook journeys that would have had a worldwide impact today. In the 13th century the world was very small, and Ramon Llull travelled its length and breadth: from the time of his first trip to Montpellier to his last voyage to Tunis, the word of God guided Llull from Santiago de Compostela to the Vienna of the Dauphinate, from Rome to Paris, from Pisa to Lyon, Genoa, Barcelona, Bougie and Jerusalem… To Ramon Llull there were no borders to hinder the dissemination of his message.

Ramon Llull has a special connection with the number three

Ramon Llull lived in a world where three religions converged: the Christian, Jewish and Muslim. He wrote in three languages: Catalan, Latin and Arabic (although no manuscripts survive in the latter). He used three symbols: the tree, the ladder and geometric figures. He asked for his works to be kept in three places: Paris, Genoa and Mallorca. He wrote a book that had three sages as its central figures, The Book of the Gentile and the Three Sages. It defines the three virtues of the soul: memory, understanding and will. In medieval culture, three is a perfect number that symbolises continuous movement and is also the symbol of the Trinity. To Llull, God was pure movement and the reason why things combined. Three is God.

Ramon Llull worked in every literary genre

Spending one’s entire life writing the “best book in the world”, as he defined it, may have been a little boring. That’s why Llull chose to put across his message in every possible way. He wrote a book on mysticism (Book of Contemplation), a novel (Felix or the Book of Wonders) and a chivalresque novel (Book of the Order of Chivalry), poetry (Song of Ramon), a book of grammar (New Rhetoric), a book of aphorisms, the Book of the Lover and the Beloved, a treatise on astronomy and, first and foremost, works on philosophy, such as the Ars Magna. And not forgetting his troubadour poems, none of which survive.

Unbeknown to him, Ramon Llull invented the calculator (and, in passing, the web)

Throughout his life, Ramon Llull was obsessed with one subject: disseminating the word of God and converting sinners (that is, the Jews and Muslims) into Christians. That’s why he invented an Ars combinatoria, a thinking machine, which enabled people to attain divine thinking. Three centuries later (the number three crops up again), Leibniz created a calculating machine based on Llull’s philosophy. This machine can also be seen at the exhibition. Lull’s combinatorial system is also the basis for the system of networks, meaning that, for Llull, “being means being connected”.

Ramon Llull is an influencer

Ramon Llull’s dream has reached us today through literature and art. For instance, Jorge Luis Borges wrote a short story entitled Ramon Llull’s Thinking Machine. Umberto Eco devoted many pages to Llull in The Search for the Perfect Language. Juan Eduardo Cirlot explored the permutations of language, and the poetry collective Oulipo published One Hundred Billion Poems, based on the combinatorial system. Salvador Dalí staged a performance “following Ramon Llull’s archangelic doctrine”…

Ramon Llull, is, therefore, a multifaceted, complex and fascinating person. The creator of a new way of thinking who was ahead of his time and has become our contemporary. We can’t think of any better reason to come and see The thinking machine. Ramon Llull and the Ars combinatoria, open from July 14 to September 11.

Nobel Laureates in Literature who have visited the CCCB

May 17th, 2016 CCCB No CommentsThe Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona’s interest in literature is very much present in its programme, from exhibitions to debates, in performative activities such as Slam Poetry and in consolidated festivals such as Kosmopolis, Primera Persona and Món Llibre. The CCCB is writers’ territory and this spring among the interesting authors visiting us are Juan Marsé, Jordi Puntí, Renata Adler, John Irving, Don DeLillo and Svetlana Alexievich. Taking advantage of the visit by the Nobel Laureate in Literature of 2015, we have done a little archaeological digging in our archive to remember other writers who have visited the CCCB and were also winners of this prestigious accolade.

Svetlana Alexievich Nobel Prize in Literature 2015. She visited the CCCB on May 2016 in a conversation with writer Francesc Serés.

Herta Müller Nobel Prize in Literature 2009 – She visited the CCCB in June 2012. She gave the lecture “Language as Homeland” and talked with translator and literary critic Cecilia Dreymüller. To coincide with her presence at the Centre, a small-format exhibition was dedicated to her “Herta Müller: The Vicious Circle of Words”.

Orham Pamuk. Nobel Prize in Literature 2006. He visited the CCCB in January 2010. The celebrated Turkish writer gave an interesting lecture on the future of museums and of novels.

J.M.Coetzee. Nobel Prize in Literature 2003. He made a “virtual” visit to the CCCB in October 2008. The South African writer read some excerpts from his book “Diary of A Bad Year” exclusively for the Kosmopolis literature festival.

Gao Xingjian. Nobel Prize in Literature 2000. Visited the CCCB in October 2008. The Chinese writer talked about the reason for being of literature and the sacrifices involved in the defence of creative freedom against the abuses of political or media power. The CCCB devoted an exhibition to him along with a television programme “Soy Cámara. El mundo de Gao”

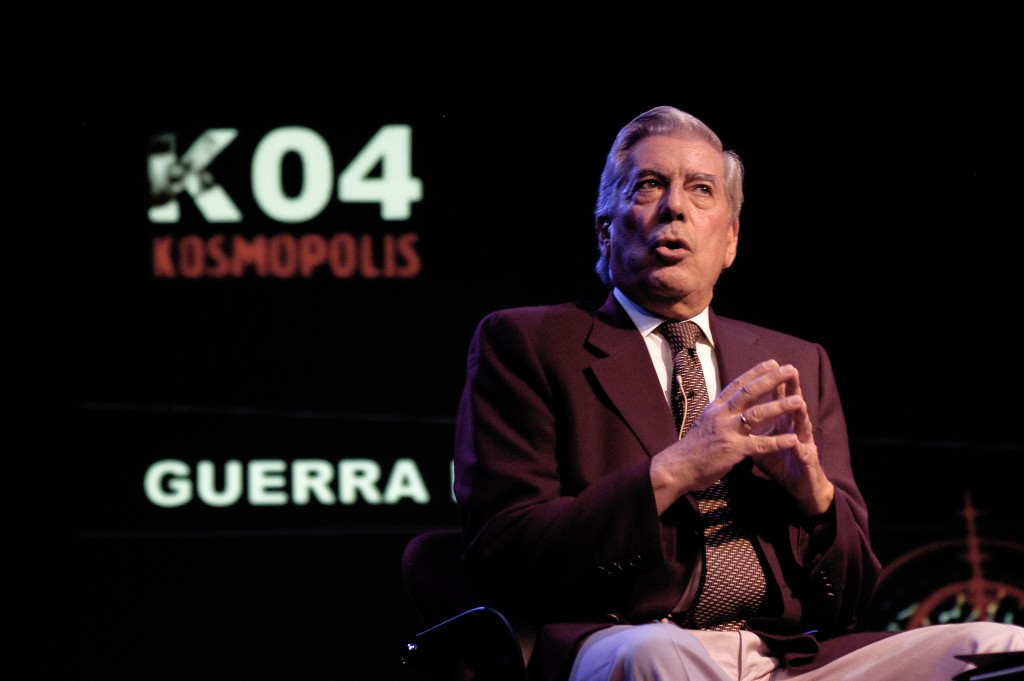

Mario Vargas Llosa. Nobel Prize in Literature 2010. He visited the CCCB in October 2004.