Pen and paper, The Netherlands, 1937 | Nationaal Archief | Public Domain

Does it still make sense to invoke literary originality in the internet era? Kenneth Goldsmith spoke about this at the Festival Internacional du Livre de Arte et du Film de Perpignan (FILAF) this summer. Alicia Kopf tells us about it in his article on appropriationism, intertextual dialogue and literary practice from a curatorial point of view in which there is room for textual emancipation and shared inspiration. Her account ends with an excerpt from an unpublished poem by Goldsmith. This week, Kenneth Goldsmith will be at the CCCB as a guest of The Influencers festival.

“The world is full of texts, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.”

Kenneth Goldsmith starts his famous book Uncreative Writing with a play on a quote by conceptual artist Douglas Huebler, who was referring to the overabundance of objects rather than texts.

Intrigued by the practical implementation of this premise, I take myself along to the FILAF (Festival International du Livre de Arte et du Film) artbook fair in Perpignan to listen to Goldsmith, poet and founder of Ubu Web, who is one of this year’s guests of honour.

FILAF brings together leading experts on artists’ books and screens films and documentaries on the subject of art. Past speakers include distinguished figures such as Sophie Calle, Juergen Teller, Agnès Varda, Albert Serra and Michel Houllebeqc, and Enrique Vila-Matas, Mathias Enard and Goldsmith were among this year’s guests.

Kenneth Goldsmith is famous for applying the appropriationist strategies of conceptual art to literature (causing a certain stir in the process). “Writing is moving information from one place to another,” he says. And he means it literally: in one of his best-known works, “Day”, trying to be as uncreative as possible, Goldsmith chose a day at random, copied out the entire New York Times, word for word, and published it as a nine-hundred page book. In a later work entitled “The Day”, he repeated the same process, this time choosing a significant date – September 11, 2001. Goldsmith aims to show that even acts that seem to have no apparent signs of subjectivity, like simply copying, are full of authorial decisions (why do I choose this text? in what space/time context will it appear? what kind of typography and layout will it have?) He points out that language – and the medium – is never an innocent carrier of meaning and that it varies enormously according to the context and the frame. The gesture of copying out an entire newspaper from a day chosen at random, or of copying out a newspaper from a date such as September 11, 2001, give rise to different readings. We could even describe them as a “homage”: a homage through the meticulous copying out of all the mundane, dramatic, and important events of any given day. A homage to the victims, in the case of 9/11, through the gesture of re-reading and re-typing a tragic series of events in an act of conscious awareness. Goldsmith shuns subjective intentionality: “The idea of a poetics of expression on the internet is absurd. Self-expression on the internet is like adding a few drops to the sea. Why not dive into the existing content? Why not move the text, make it come to the surface?” Roland Barthe’s death of the author, and theories of the disappearance of the author (Michel Foucault in “What is an Author?”) resonate at the bottom of Goldsmith’s aesthetic ocean; while imposing an author on a text is like “imposing a limit” of interpretation, etymologically “text” comes from “textile” or a “thing woven” – in this case, a fabric of quotes that Goldsmith has unified, ordered, and merged into the voice that writes. Foucault quotes Samual Beckett to formulate the subject when he writes about “the function of the author” “’What does it matter who is speaking,’ someone said, ‘what does it matter who is speaking.’”

As any reader who is superficially conversant with modern and contemporary art will know, the reuse and appropriation of materials is a tradition with an illustrious lineage: Picasso’s collages, Duchamp’s fountain, Walter Benjamins Passagenwerk and the practices of avant-garde group OuLiPo, for instance. We are not questioning the merit of these artists/writers in the bold combination of references and the broadening of the spectator’s field of perception beyond the physical authorship of the works (or in Benjamin’s case, the texts). Subjectivity, or individual expression, is not just the synthesis of influences that an author uses in his work (we know that originality does not exist, only the boldness of combining elements in a new way). Instead, it comes through in the choice, and in the combinationatory skill of the curator or installation artist, in what we could call a “second hand” expression. The provocation – the element that forces spectators to rethink what we consider “art” – often opens a gap in which the real enters the the symbolic realm (or vice versa), which is the basis of any avant-garde work, and perhaps of the modern philosophical project (aren’t all our lives supposed to be works of art? aren’t artists supposed to give us tools for this?)

“People’s idea of art is infinite, whereas their idea of poetry is very limited. Poetry is such an easy place to go in and break up the house. The avant-garde loves to destroy things, and I’m an old-school avant-gardist.”Goldsmith at Wilkinson, 2015

In one of the most sacred bastions of the “authority” of writing, Goldsmith gives writers the status of information DJs: “My cutting and pasting is an acknowledgement of this. I’m dead serious that this is writing now. You may not want to hear that or think of it as writing, but I’m telling you that the moving of information is a literary act in and of itself,” he says. Elsewhere he adds “appropriation is bound to become just another tool in the writer’s toolbox.”

Goldsmith, who clearly has a deterministic and optimistic view of technology (“Facebook is the world’s autobiography”), has invented new methods for teaching writing, such as encouraging his students to become digital flaneurs and use the internet as a legitimate source of inspiration. Turning his back on the Romantic imaginary, Goldsmith compares writers to software programmers (although anybody who has had to design their own website will wonder whether code can express anything more than an order).

Paradoxically, academic writing – a paradigm of authority – is one of the most obvious examples of intertextual dialogue, based on appropriation and intertextuality (text displacements). It is a kind of collage-dialogue between the author and the scientific community or scholarly tradition, under the normative system of the quote. Style, Goldsmith says, is about how we organize certain information, and context is the new content, “how I manage it [information], how I parse it, how I organize it, how I distribute it, is what distinguishes my, writing from yours.” Hypertextuality, social media, search engines, websites and apps generate new information distribution architectures, a new realm of exploration for the poet: “The internet is the greatest readymade”.

Goldsmith’s ideas about context in the visual arts, which is the discipline he studied, are just as unconventional as that of his literature: “Museums have become social spaces; nobody looks at the artworks, at most people take selfies with them, and exhibitions happen through instagram.”

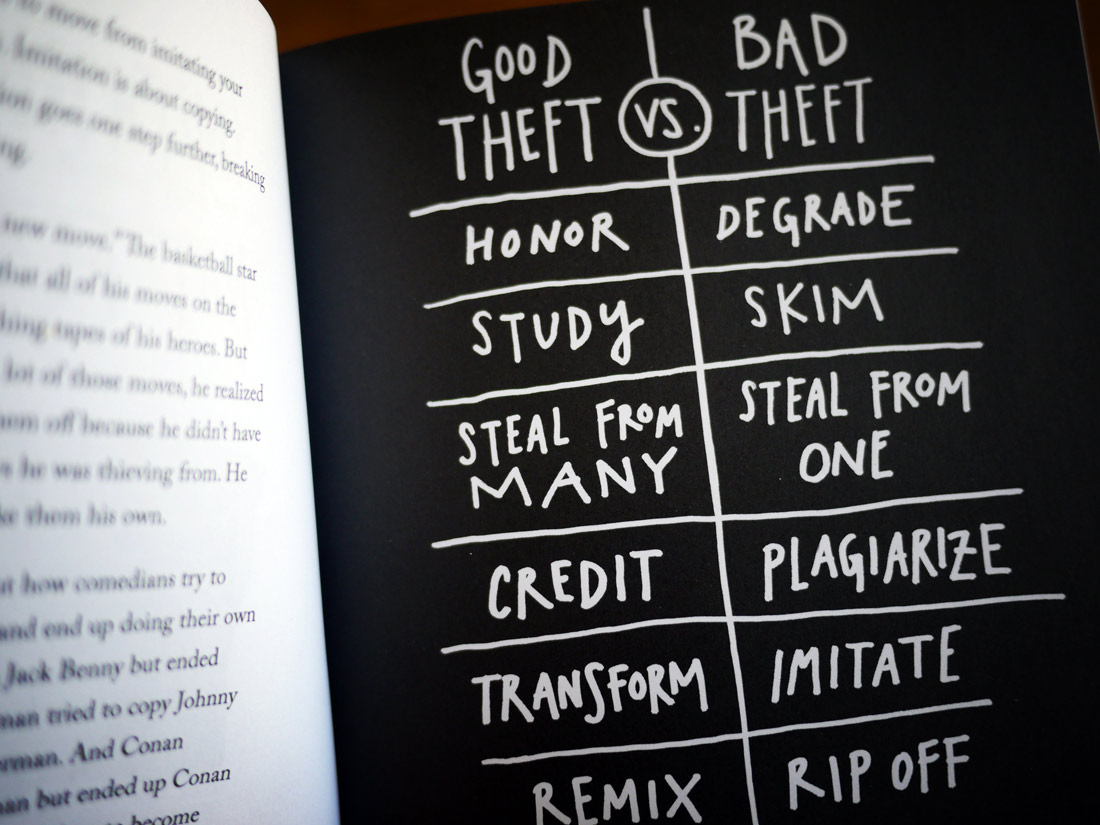

Steal Like An Artist | Austin Kleon, Flickr | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When it comes to his appropriation works, reading Goldsmith could seem boring. A journalist from New Yorker magazine recently asked him “if your work is boring and horrible to read, why are you invited to the White House?” To which he replied “Because I’m a charismatic performer.” He’s not wrong, if what we saw yesterday is anything to go by. Far from a litany of tedious lists or newspaper items, the reading was an not only an aesthetic manifesto but, given the almost epic nature of the text – written by Goldsmith – and the excellent diction, almost moving. A paradox? Let’s listen:

Poetry is not public policy.

Poetry has neither a public nor a policy.

Poetry’s power is its powerlessness,

which is the power to imagine the unimaginable.

Poetry’s inability to change anything

is its ability, it’s disability its acuity.Poetry’s inversion of logic is its logic,

its stasis it’s movement,

its impoverishment its wealth.(…)

Poetry thrives on speculation,

proposition its fulfillment.

In this way, poetry is completely conceptual;

I think it, it exists.

No permission needed.

Ask no one.No gatekeepers necessary

because there’s nothing there to protect,

it’s all there for the taking.In this way, poetry is completely romantic;

I dream it, it exists.

In this way dreaming is democratic.

Everyone dreams and everyone dreams at no cost.

In this way, there is nothing elitist about dreaming.

My nightly dreams are no better than yours.

My nightly dreams are worth no more than yours.

My dreams are no more causal than yours.

My nightly dreams are as unrealizable as yours.

They’re dreams, after all;

they mean a lot to you and to me,

but mean little to anyone else.Who cares? Would you forego dreaming?

‘Pataphysics is foundational to poetry.

It’s the base of the deal.

The science of imaginary solutions to imaginary problems

is definitive.

Your problems are imaginary;

so are your solutions.

Give it up. Let it go.

In this way,

let the illogic become logical.

Illogic as resistance.

Dissolve binaries,

live in the gray zone.

As an inversion, functionless

becomes functional, radical, changeable.But ‘pataphysics is a bad way to conduct social justice.

In the real world, real solutions are required for real problems.

This is not poetry’s work.

Poetry’s work is to jam systems with irrationality,

with illogic and abstraction.

This is where it works best.

Take to the streets, yell at the top of your lungs for change.

You will make a difference.But don’t put that burden on poetry,

for poetry is reversed engineered for self-destruction.

Bombs will explode.

But nobody will get hurt.

Mistaking poetry for politics

is a result of a malfunctioning spellcheck.

Poetry’s ethics is aethics:

malleable, soft, playful and speculative.Theft without consequence.

Compassionate anarchy.

We’ve got water pistols.

Hands up!

This is a robbery!

We’re striking Jeffersonian candles.

Please, take my flame.(…)

Poetry’s ethics is aethics:

malleable, soft, playful and speculative.(…)

Theft without consequence.

(…)

Draw from the common bank account,

empty and therefore symbolic.Appropriation has three definitions:

monetary appropriation,

aesthetic appropriation,

and straight up theft.Try not to mistake your poetic metaphors for reality.

There’s no violence in cutting text, dear (…)Cutting text is in no way like cutting flesh.

(…)

Kenneth Goldsmith

Fragment of the poem “Poetry is not Public Policy”, translated by the author from a reading by Kenneth Goldsmith during the cermony at which he received an honour award from the FILAF International Art Book and Film Festival, June 2016.

Leave a comment